Some notes on the production of Blue Celadon Glazes

Here are two ways to get a decent blue celadon…there are more, but these are the ones that I am responsible for.

The easy one first. It is called Coburn, named after the color of a little girls eyes that was visiting the gallery with her dad…many years ago. Her name was Coburn, which seemed perfect to me.

Just omit the iron oxide in HH celadon and add a small tube of cobalt blue watercolor to the unity batch of 100 pounds. If you are making a smaller batch, just wing it with the watercolor. Make sure that you are using cobalt…and no other type of blue watercolor, as there are many to choose from. I add the cobalt watercolor from the squeeze tube into a small amount of water, and really mix it well with a palate knife and/or stiff brush so no lumps are left, then add it to the glaze. Of course, you can use the cobalt watercolor trick in lots of other glazes too…mostly they turn out sort of cute and pretty, so beware of the easy route. Of course you can add this to porcelain clay too when it is slip…lots of possibilities for slip trailing and other blue and white uses…think Wedgwood and sprigs. Think danger! The value in cobalt watercolor is the fine grind of the cobalt….it is very fine!

The best blue, Jun celadon, is of course the hardest to achieve. I worked on this glaze for many, many years before arriving at a good solid blue that did not move into the purple side of the spectrum. The Chinese name for the glaze is Jun, and it is the first glaze that escaped the Imperial grasp on glazes and got into the homes of the literati of the time. In those homes of the governing middle class were jardinières for forcing bulbs and bowls for kitchen use. In 1964 the Baguadong Official workshop in Yuxian in Henan province was found, and it is believed to be the first workshop producing Jun glazes. It started in the Tang dynasty and flourished in the Song dynasty.

As it turns out, the Jun glaze is complex. It must have a fairly high silica content, and it must be able to support phase separation, and it must be opalescent. Phase separation is critical, as the light bounced back from the glaze bubbles gives opalescence and therefore a blue glaze. The best example of phase separation may be fog…a mixture of water and air in phase separation…another is mayonnaise, where egg and oil are in phase separation. In the Jun blue celadon glaze, you have phase separation of air bubbles and glass that has a tiny amount of phosphate incorporated. The result is opal glass that is blue instead of green. The Chinese likely used wood ash as a source of phosphate in their glazes, because they had a lot of it left over from wood kilns and other heat usage. I have tried wood ash, and it works, but you also get a lot of other “stuff” with the ash, so it is less dependable. I use bone ash for my source of phosphate. It should be ground with a mortar and pestle to a dust before being added to this glaze.

I had the good fortune to meet Robert Tichane, the author of Those Celadon Blues. He gave me a very helpful push in the right direction when he found out that we were both working on a Jun celadon. While his glazes worked, they did poorly in my kiln. I ended up mixing his information with mine, to arrive at the Jun glaze below…could not have done it without him, so thank you once again Robert. I also had help at the Royal Ontario Museum where the curator of the Chinese ceramics section, Ms. Pattie Proctor allowed me to carefully inspect the Jun and Song shards in the museum’s collection….Thank you Pattie!

This glaze is a difficult one to master…it is on the edge of running off the vase or bowl, and it also needs to be applied fairly thickly to be at its best…so beware and take some precautions when you try it. Put a clay “cookie” under your piece in the firing, and be sure to give it a good sprinkle of silica sand so the pieces will separate after. It is OK when it is thin, but really, why would you go for OK when you can really have a thick, unctuous, wonderful juicy Jun in the palm of your hand? Go for thick!

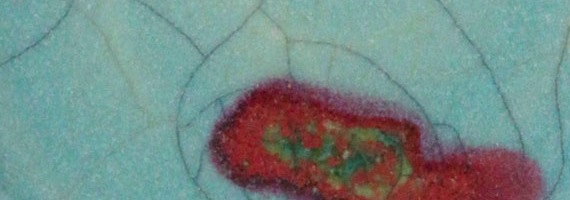

Of course, if you want to play like the Chinese did, add some copper splashes or copper brush work to your bisque piece before or after glazing it with Jun…a little strand of copper wire draped around the bowl, or on the shoulder of a vase is interesting, and a few filings of copper sometime yield good results too. You can also use your copper red glazes for decorating too. Be prepared for disaster, and happy at the same time…

Be very careful to cool this glass very slowly…ever so slowly…the bubbles need to stay in the glass, and the glass needs to be thick, so go have some fun while the kiln is cooling, and be patient. I use at least two days of cooling from cone 13 to not hurting your hands as a rule of thumb.

You will notice, that this glaze is also a crackle Jun Celadon, so feel very free to give the piece a wipe of India ink for maximum effect. The piece must be dry, and you will need a pair of rubber gloves and a rinse bucket. The rubber gloves do two things…keeps the moisture from your hands off the pot, and keeps your hands from being all inky…the importance of keeping the surface dry cannot be over stated…you only get one chance to do this right.

Glove up, and apply the ink directly with a rag loaded with ink, and just as it is starting to dry, use a fresh damp rag to wipe off the excess then rinse. You will need to wipe it again later to get rid of the last skim of ink on the surface. Good India ink has a little bit of gelatin or shellac in the mix, so it will dry and stay that way in the fine crackles. Of course you can use other inks too, but some are soluble so each time the piece is dampened, some color may leave.

In Table 1 below, you’ll find the batch recipe for 100lbs of Jun Celadon glaze. This Jun glaze likes the cooler part of a cone 13 kiln…cone ll and 12 should be fine.

Table 1. June Celadon 1991 using G200 purchased before 2009

| Clay Body Component | lbs/% |

|---|---|

| G 200 Feldspar | 40.09 |

| 40um Silica | 34 |

| Whiting | 15.32 |

| Dolomite | 3.83 |

| Grolleg Kaolin | 3.83 |

| Bone Ash | 0.63 |

| Bentonite | 0.63 |

| Iron Oxide | 1.67 |

| Total | 100 |